Art Journey Stories - 15 February 2020

It might seem like the bonds between the ancient Egyptian civilization and Paris started as a result of Bonaparte's campaign of 1798, or with Champollion deciphering the hieroglyphic system and creating the Louvre's Department of Egyptian Antiquities. Instead, this story started well over 2,000 years ago.

Parc Monceau pyramid, photo © Art Journey Paris.

Paris, Par-Isis?

The Roman Empire was so vast that once it encompassed London and Babylon, all the way to Morocco. And since Egypt became part of this mighty Empire, the worship of some of its divinities travelled along with its expansion. This is how a small town near the Seine river ended having temples dedicated to the goddess Isis.

What was this city's name? The earliest historical trace came from Julius Caesar, whose troops invaded in 52 BC a place described as "Lutetia, a town of the Parisii, situated on an island in the river Seine".

The origin of the name of the people, Parisii, is unclear, as well as the name of the town, Lutetia. In 360 AD Julian the Apostate became Emperor during his stay in Lutetia Parisiorum, and the city started to be called Paris. The first King of France, Clovis, made Paris his capital in 508 AD.

Ever since, historians have suggested numerous interpretations for the origins of the name Paris, one of them based on the Trojan War's hero Paris. Another suggestion was based on the fact that the ancient Egyptian goddess Isis was worshipped in Paris, and might have given her name to the city.

It only is a theory, but an interesting one, which needs explanation. Even as the meaning of hieroglyphs was lost, the memory of Isis' worship persisted, so when a historian wrote about the Viking invasions late 9th century, he called the city "formerly Lutèce, since you took your name from Isia … the world calls you Paris, as if it said quasi par Isae (similar to Isia)".

In 1532, a historian listed the different opinions as to the origin of the name Paris, and attested that "some say near Saint Germain des Prés there was a temple dedicated to an idol of the goddess Isis" and added "this is true as several people of our time have seen the statue, and it is quite big", although it had since disappeared. He then goes on to explain the city was called "Parisis, quasi par Ysis".

So the Latin quasi par Isis (similar to Isis) was considered one of the potential origins of the name Paris.

The 1811 coat of arms of the city of Paris, with at the prow of the ship, the ancient Egyptian goddess Isis. She sits on a throne, and the hieroglyph for throne ???? happens to be her name.

In 1773 came the suggestion that in the heart of Paris, there "was the Temple of Isis, on whose ruins the church of Notre Dame was raised". Further, as she was considered the goddess of navigation, a ship was used as a symbol of Isis, so "the name of this vessel also became the name of the city: its name was Baris, with the strong pronunciation of Northern Gaul, Paris".

This tradition is likely how Isis ended, in 1811, on the coat of arms of the city of Paris, seated on the prow of the ship of Paris. Soon after the fall of Napoléon, the shield was replaced, but for a short time, the names of Paris and Isis were officially linked.

Moreover, as Napoléon's invasion led to the discovery of the Rosetta Stone, a young man, Jean-François Champollion, joined the other great minds of the time in the race to decipher Egyptian hieroglyphs.

While still a teenager, he learned over ten ancient languages, one of which, Coptic, was based on the language spoken by the ancient Egyptians. Eventually, in 1822, his efforts were rewarded, as he became the first man in 1,400 years able to read hieroglyphs, later to become the first curator of the Louvre Egyptian department.

So thanks to Champollion, we now know that in ancient Egyptian ???? ???? Pr Isis (pronounced Per or Par Isis), actually means House of Isis, as if the memory of a temple of Isis somehow led to Paris' name.

Even if it is only a legend, it is fascinating to ponder at the potential link between Par Isis and Paris, as being named after an Egyptian goddess would be more prestigious than the potential meaning of Lutetia, "marsh" or "swamp".

Obelisks, sphinxes and the return of Isis

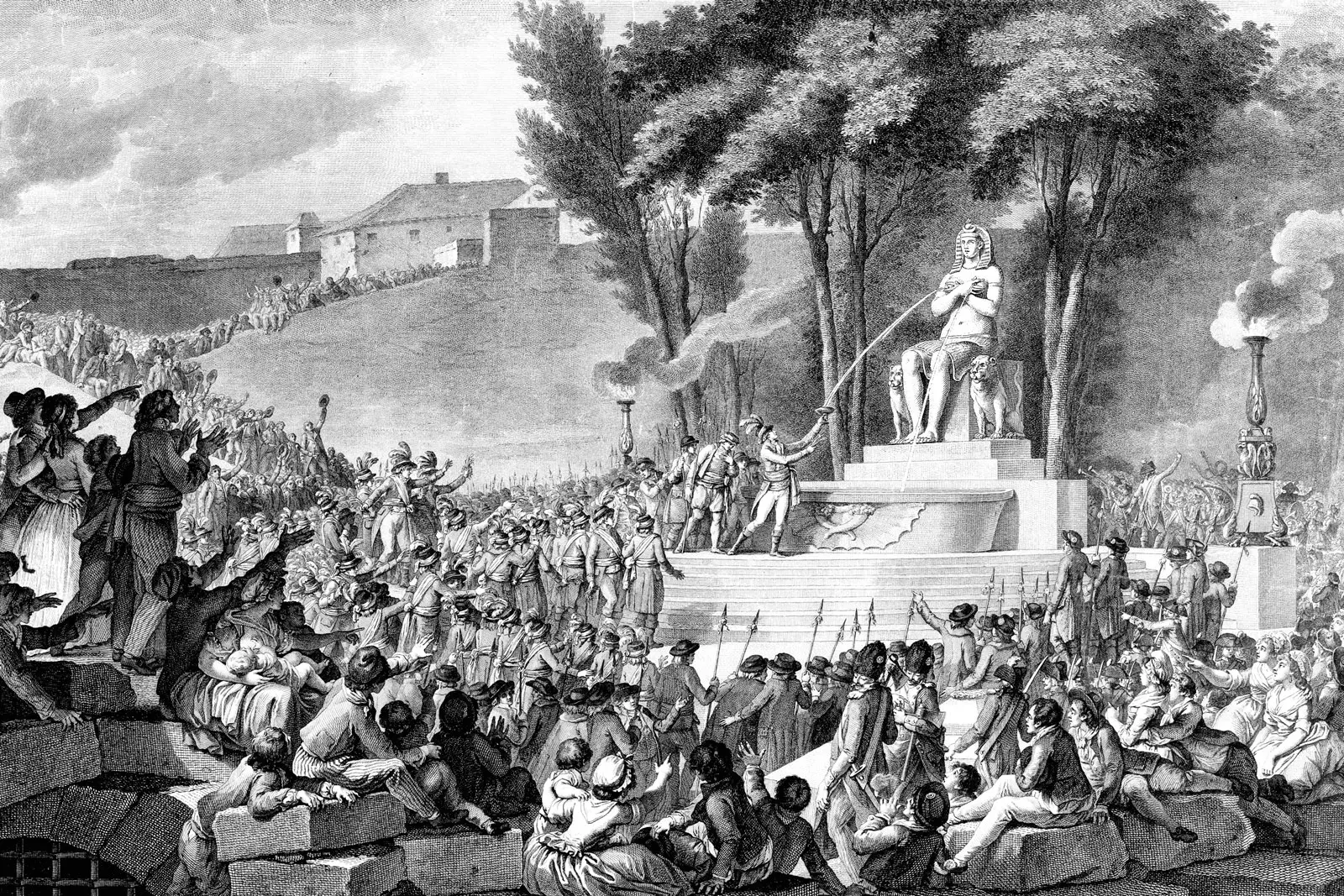

1793 Paris, on the ruins of the Bastille, the return of the ancient Egyptian goddess Isis, as mother Nature. She regenerated elder delegates from all French regions, by drinking her nourishing water. Plutarch informed that "Isis is, in fact, the female principle of Nature, and is receptive of every form of generation".

With the Renaissance, trying to emulate Rome, a city covered with Egyptian obelisks and sphinxes, Paris was indirectly looking towards Egypt. The first obelisk of Paris was erected in 1549, to celebrate the arrival of King Henri II. Louis XIV had an Arc of Triumph decorated with four obelisks.

As for sphinxes, a stroll up and down the city would reveal the countless sphinxes in courtyards, door or window frames that started to adorn Paris from the 17th century. In 1768 a proposal was made to erect an obelisk on the hill where the Arc of Triomphe would eventually be built.

And with the French Revolution, somehow Isis made an official return to Paris. In 1793 statues and fountains were erected to celebrate the end of the monarchy. One of them, called "Regeneration", was Nature depicted as Isis "regenerating" the elderly, who drank the water sprayed by the ancient goddess.

Two years later there already was a proposal to erect an obelisk Place de la Concorde. Then in 1801 came a proposal for two obelisks, and, not to be outdone, another for four obelisks…

Ramses II obelisk Place de la Concorde

Left, the obelisk at the entrance of Luxor temple, with two statues of Ramses. Right, the obelisk place de la Concorde. Both are petrified rays of the sun, Ra, the father of Ramses. Photo © Art Journey Paris.

In 1830, with the Pasha of Egypt offering France the two obelisks at the entrance of the magnificent temple of Luxor, Paris got a chance to be adorned not by a pretend obelisk, but by the real thing, carved on the orders of Ramses the Great.

There only was the slight problem of transporting a 230-ton monolith down the Nile, across the Mediterranean, the Atlantic coast, and up the Seine river. The Egyptians managed to transport stones up to 1,000 tons down the Nile, the Romans, in turn, transport obelisks to Rome, but such endeavors hadn't been done for well over 1,500 years.

A special boat had to be built for the occasion, set to travel 7,500 miles for nearly three years. Finally, in 1836, the Parisian public watched as the obelisk was slowly erected in the center of Place de la Concorde.

After such an arduous journey, this was the most perilous operation, as the obelisk, already cracked, could easily have snapped. While an orchestra played Mozart Isis' Mysteries, a cracking sound was heard, but fortunately it only was a piece of wood. Ramses II's obelisk, in the center of one of the most prestigious squares of Paris, is the city's oldest monument.

Parisian pyramids

Seen from the Louvre, the great perspective ends on the horizon, with the great Arch of la Défense. Built along the curvature of the Seine river during eight centuries, the Louvre palace is slightly off center, so the actual start of the perspective is the statue of the Sun King, Louis XIV, just in front of Pei's pyramid. Photo © Art Journey Paris.

The first Parisian pyramid was built in 1779 as part of an exotic garden, with a medieval castle, a farm, a Dutch windmill, the ruins of a Roman Temple, Chinese and Turkish style amusements, an obelisk, and a "wood of the tombs". This is how an "Egyptian tomb", a pyramid, was built with a statue of Isis inside.

While the first pyramid was commissioned by a noble, the second one was, as tradition dictates, commissioned by the modern equivalent of Pharaoh, the French President. Fascinated by the work of Ieoh Ming Pei at Washington's National Gallery, François Mitterrand chose Pei to design a new entrance to the Louvre museum, succeeding the Kings and Emperors who had built the Louvre since 1190.

The idea was to double the size of the museum, and create an entrance able to receive millions of visitors. But many reacted with horror at the prospect of replacing a car park with a glass pyramid, and the scandal earned the President nicknames like "Pharaoh", "the Sphinx" and "Mitteramses". Pei, who had already won the Pritzker Prize (the equivalent of a Nobel prize for architecture), was subjected to such insults that the translator wept.

Yet Ieoh Ming Pei was actually very respectful of the site, with a design at once classical and modern. Pei himself explained that the design had nothing to do with Egypt, and that the glass pyramid was "made for life and light", and, as it is transparent, "it had the same spirit as Paris' sky".

And the pyramid would also be part of an axis — Louvre — Carrousel — Concorde obelisk — Arc de Triomphe, until the Grande Arche de la Défense, forming a line 5.5 miles long. After exactly 800 years, Pei's pyramid was like a diamond crowning a perspective built on the orders of Kings, Emperors and Presidents.

Entering the pyramid, the visitor wonders at a structure made of light, with the sun during the day, electricity at night. Inside the visitor not only discovers an amazing collection of ancient Egyptian artefacts, but that Isis is carved into the stone of the Louvre palace, as in 1806 she was added to the wall of the Cour Carrée courtyard. With a better understanding of the ancient Egyptian civilisation, Pei's pyramid might still feel like a modern interpretation of the Egyptian pyramid, in part symbolising the life-giving rays of the sun Ra.

The Parisian axis of light would, one imagine, have impressed even mighty Ramses II, during his visit of 1976. His mummy, flown to Paris to save it from decay, was received at the airport with military honours, as befits a head of State, and Ramses was driven around Place de la Concorde, to admire, one last time, his obelisk. Stuck in Parisian traffic, he might even had time to look at its hieroglyphs, glad to read that he was "King of Egypt, son of the Sun" and reassured his posterity was secure, as "the sky is your monument, your name will be as permanent as the sky".

Maybe this foreign city would have even felt familiar. After all, its people had worshipped an Egyptian goddess, it is covered in sphinxes, the Nile flows there, or at least a street named after it. Not only does it have a stone pyramid, but also five glass pyramids and a major collection of Egyptian Antiquities.

The great Pharaoh might even have felt some pride in having participated, with his obelisk, in making the City of Light, like his own achievements back home, worthy of the world's admiration.

https://artjourneyparis.com/blog/ancient-egypt-paris-story-unexpected-bonds.html |